Gallery artists

Artists exhibited

-

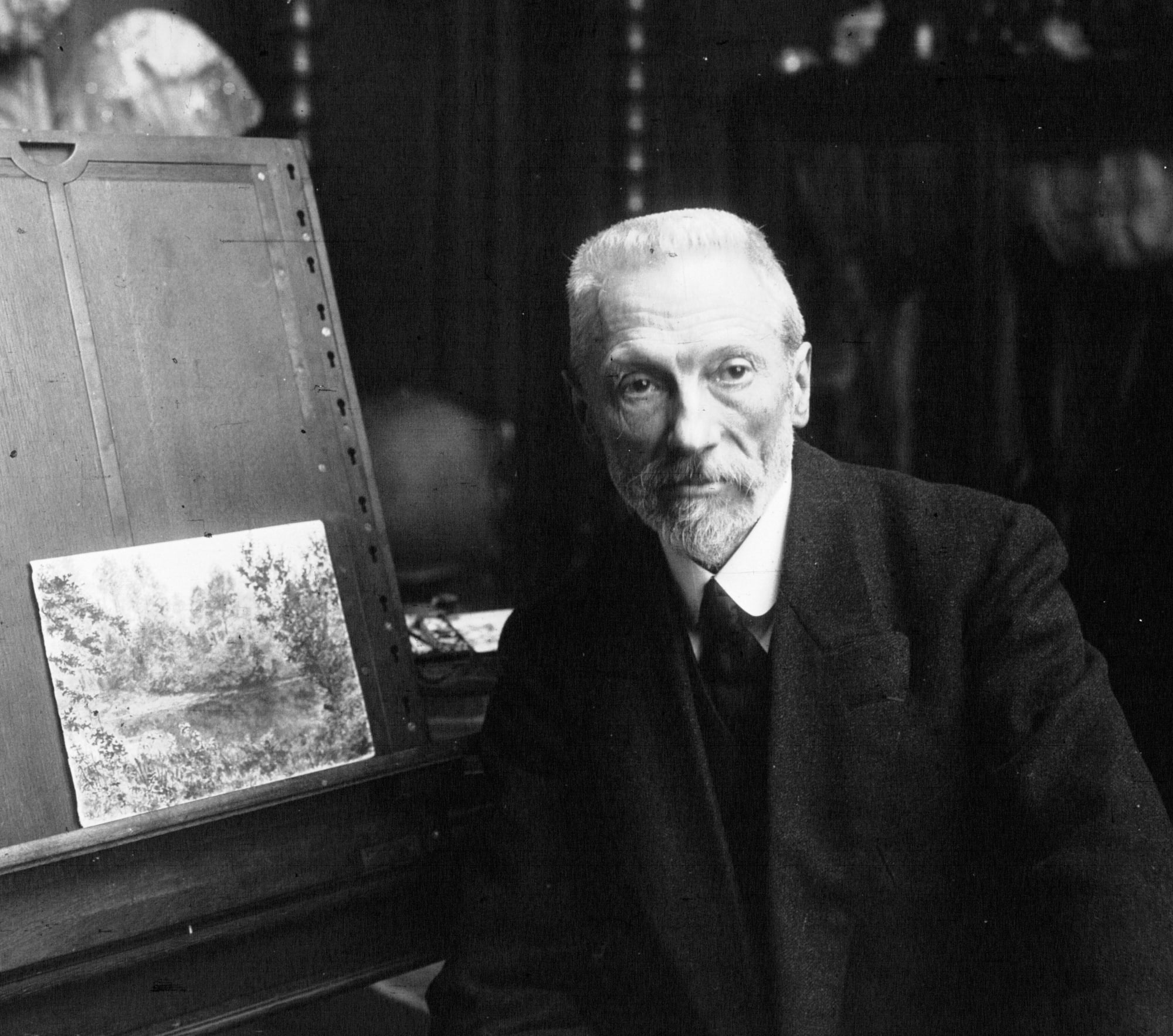

Albert Andre

-

Alexander Archipenko

-

Kenneth Armitage

-

Frank Auerbach

-

David Bomberg

-

Pierre Bonnard

-

Eugene Boudin

-

Georges Braque

-

Gustave Caillebotte

-

Alexander Calder

-

Charles Camoin

-

Paul Cezanne

-

Lynn Chadwick

-

Marc Chagall

-

Émilie Charmy

-

Edgar Degas

-

Sonia Delaunay

-

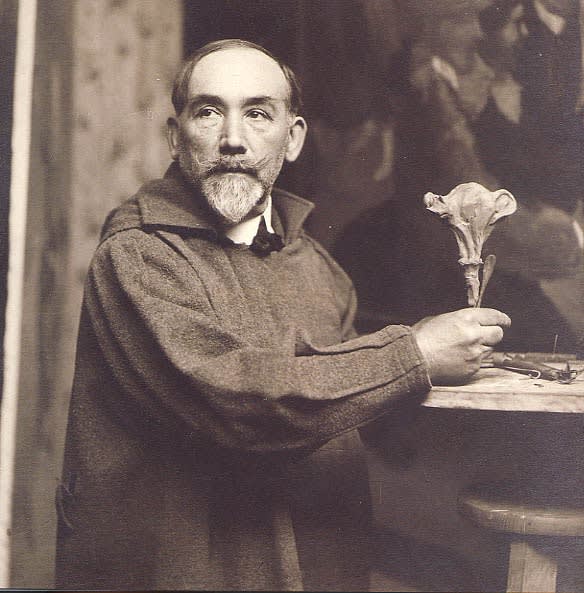

Maurice Denis

-

Kees van Dongen

-

Jean Dubuffet

-

Raoul Dufy

-

Emile-Othon Friesz

-

Paul Gauguin

-

Albert Gleizes

-

Jean Baptiste Armand Guillaumin

-

Jean Hélion

-

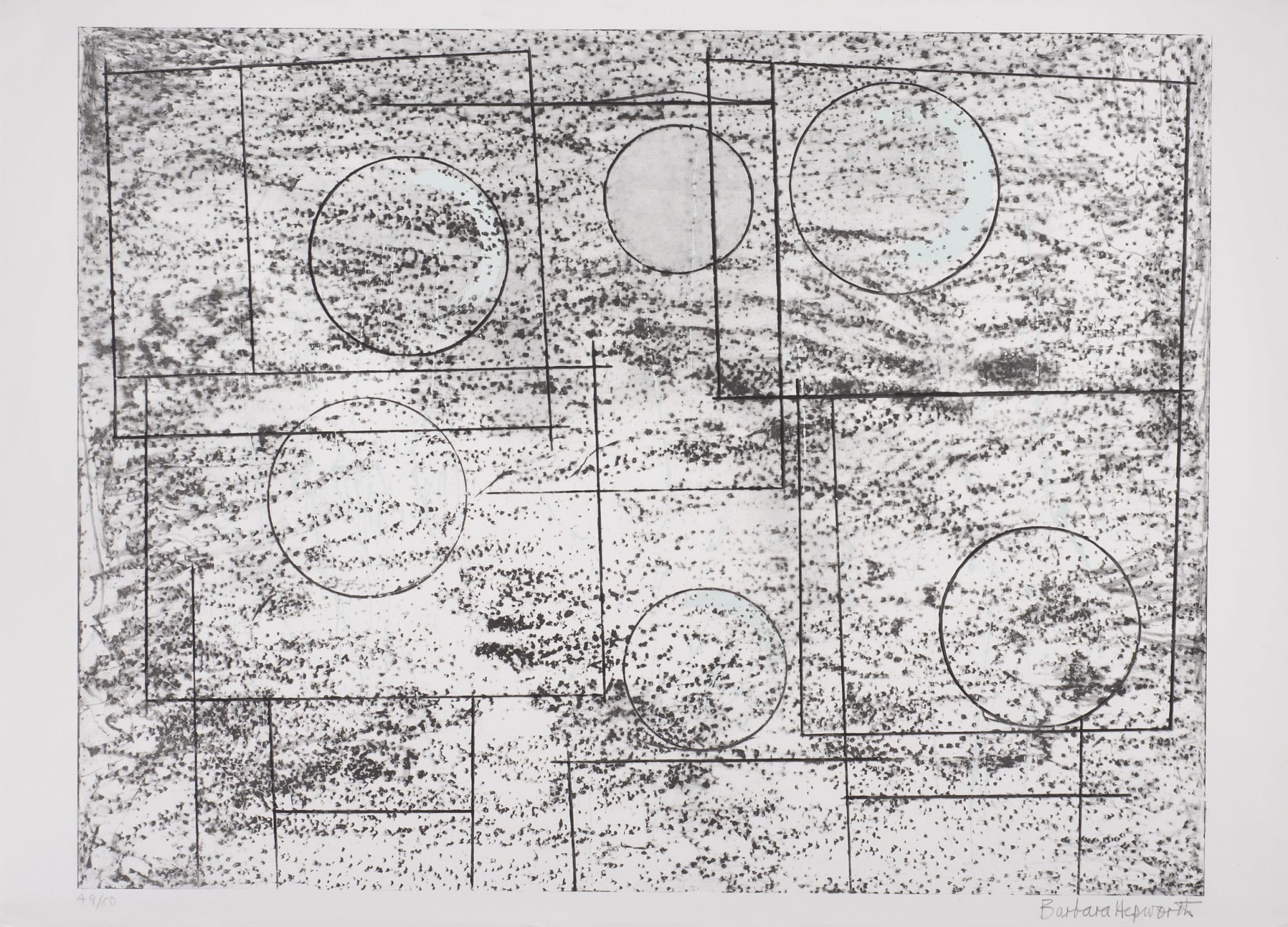

Barbara Hepworth

-

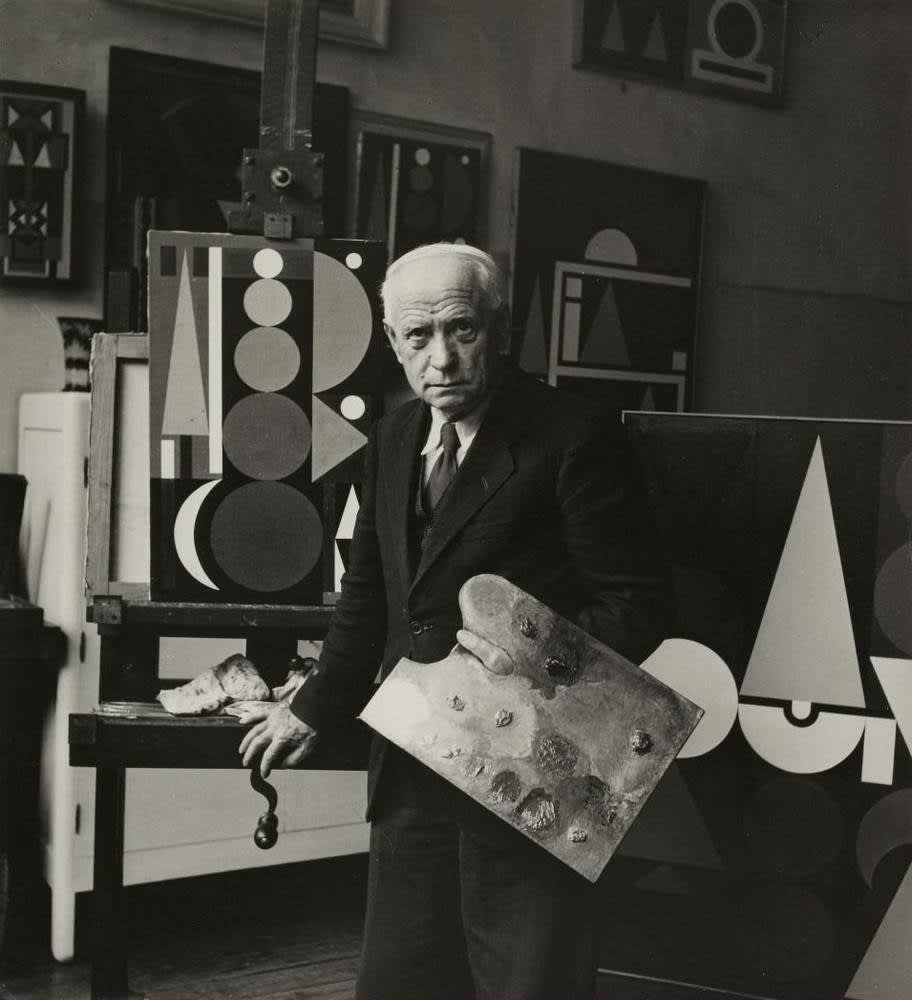

Auguste Herbin

-

David Hockney

-

Howard Hodgkin

-

Christo and Jeanne-Claude

-

Alfred Jensen

-

Béla Kádár

-

Vassily Kandinsky

-

Leon Kossoff

-

Yayoi Kusama

-

Henri Laurens

-

Henri Lebasque